Git - Internal Data Model

a dive into the internals of git where the magic happens

Overview

In the last article, we discussed an overview of git as a VCS, its history and the common commands and workflow. The common commands included the git add and git commit command. We also discussed the areas known as working directory, staging area (index) and the repository.

In this article, we will aim to go a bit deeper and understand what is happening under the hood when you run these commands. How does git take your files and store them into the repository? How does commit history get created? How do branches and tags work?

Interested to know this? Read on. Just looking for a short version? Go to the TLDR section.

What happens in.git folder when you run `git add <file>`

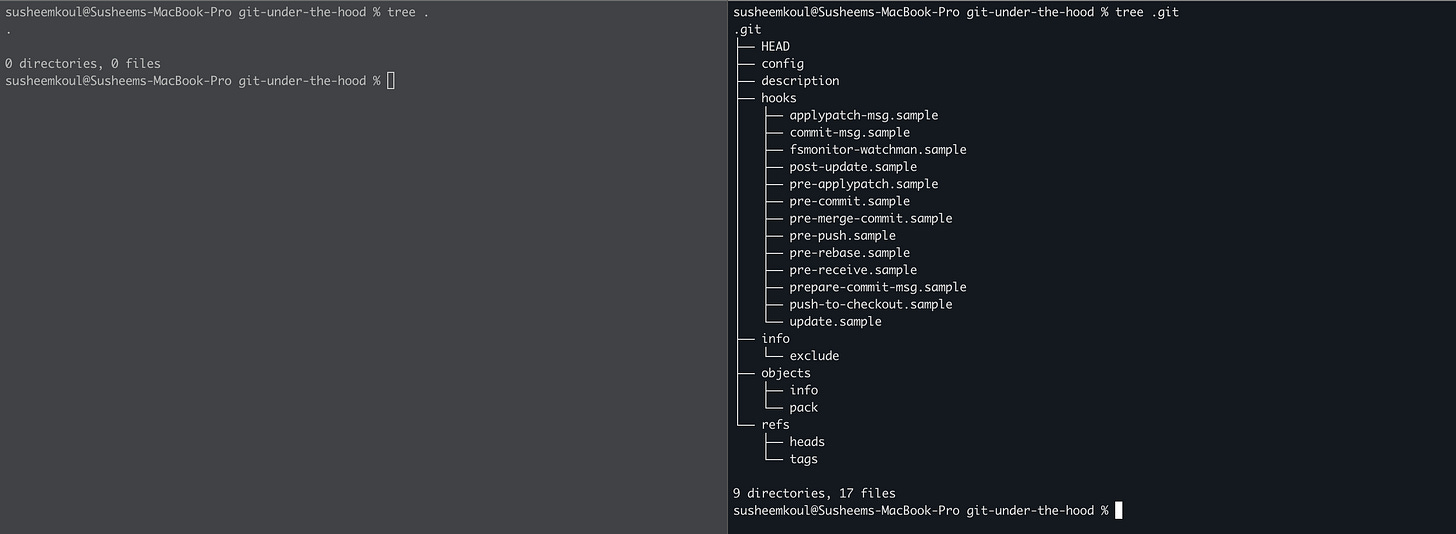

Let’s go ahead and setup a fresh git enabled project folder using git init. This is the state of the git repository at the moment. Note: All the images in this article will try to show side by side view of the .git folder (on the right) and the actual working directory tree.

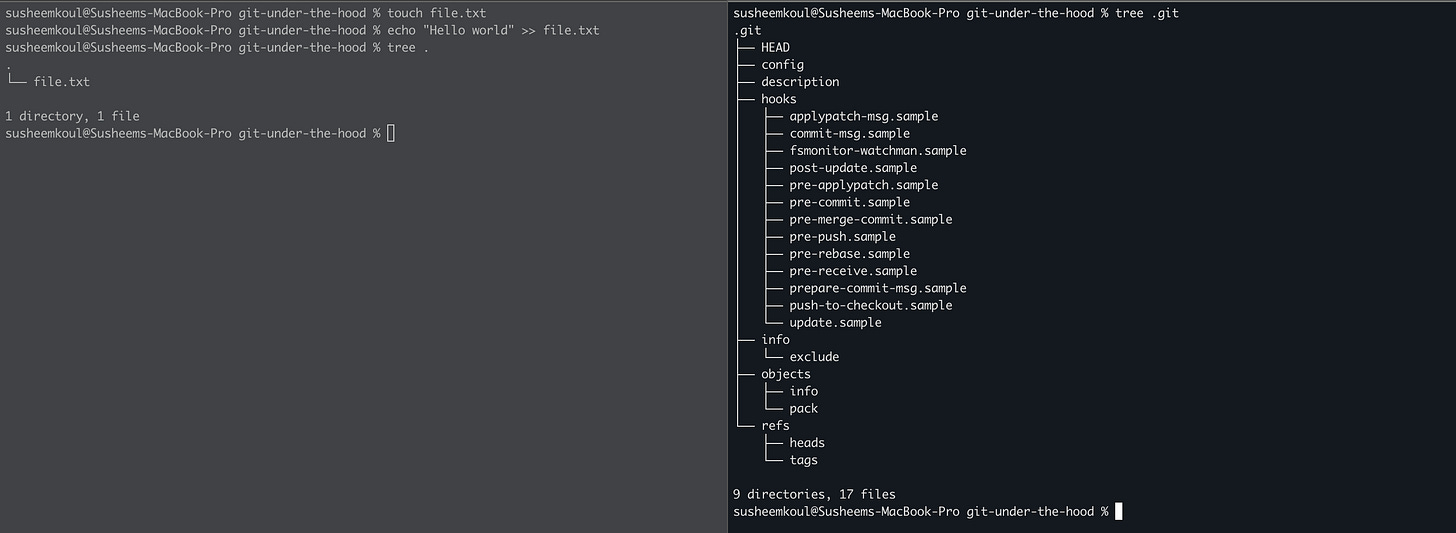

Now let’s add some files and see this view again

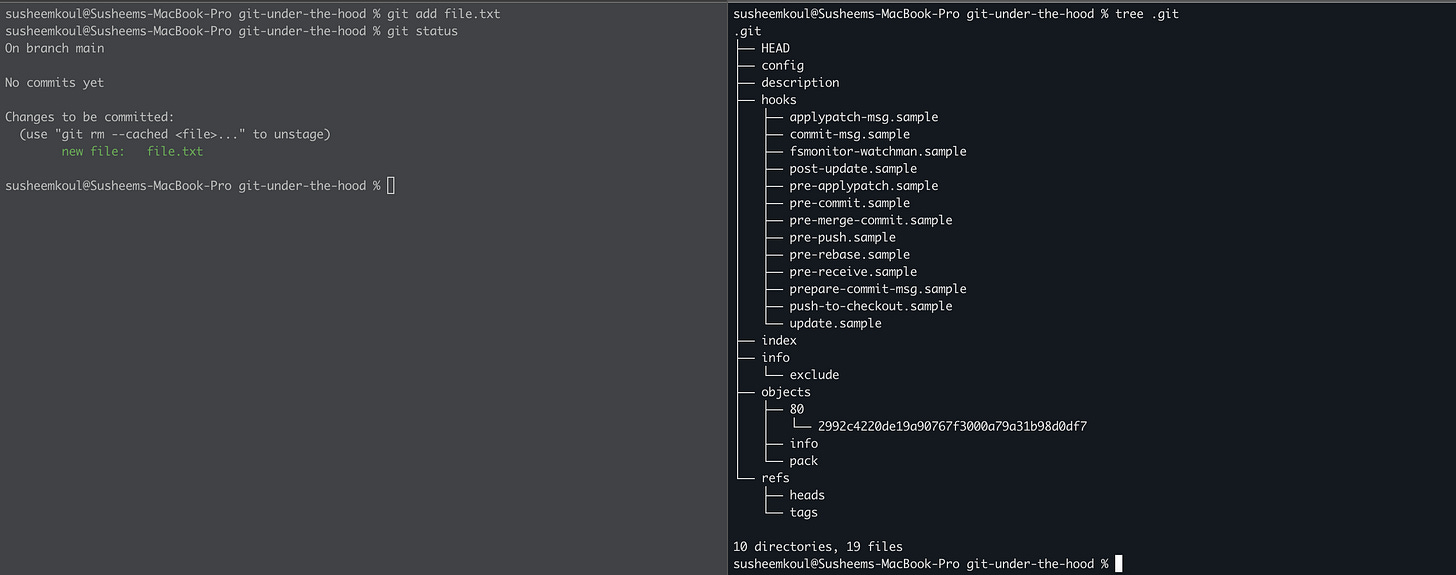

The working directory has a new file now called file.txt but the .git folder didn’t show any changes. Let’s try adding the file to the index area by running git add file.txt

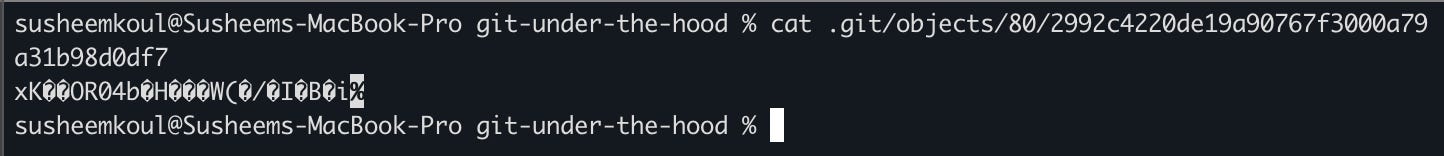

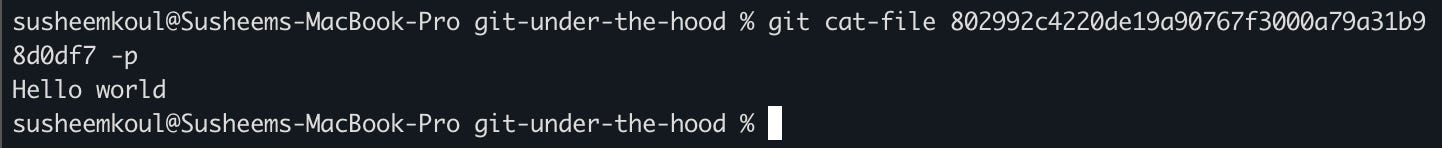

Something happened in the .git folder now! You can see under the objects directory, there is a new directory 80 which has a file in it 2992c4220de19a90767f3000a79a31b98d0df7. Let’s try to examine whats inside this file

Hmm, this looks like some alien language. Time to pull out some expert help in form of the git cat-file command.

git cat-file is a low level command that allows you to read git repository files which are generally not suitable for human viewing. The format is simply git cat-file <object-hash> -p . Object hash is constructed by appending the folder name inside git objects (80 in this case) with the file (2992c4220de19a90767f3000a79a31b98d0df7)

Let’s try running this

This looks more like it. Remember this command as it will come in handy.

Quick Sidetrack into git object store

Based on what we saw, when we added the file to the index, git created an entry in the .git/objects folder. This is where git stores most of the important stuff including your repository files and directories.

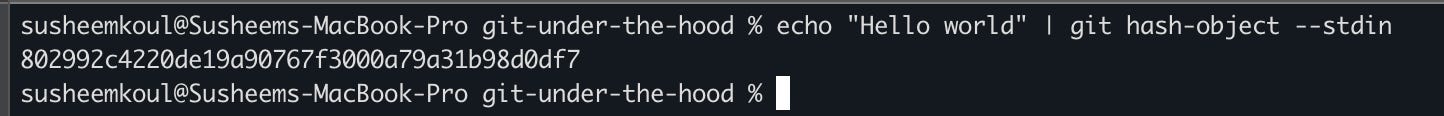

We also noticed that git created some sort of folder / file names to store our file in. This folder / file name is actually derived from a hash of the file contents. There is a utility command git hash-object which can be used to hash the contents of a file (or a given input string). Our file contained the text Hello world . This got hashed to 802992c4220de19a90767f3000a79a31b98d0df7. If we run this text through the git hash-object command, we should ideally see the same result

So internally, when adding a file to git index, the file contents are hashed and the corresponding hash is broken into a folder (first two characters) and a file name (rest of the hash). The file contents are then stored in the corresponding file / folder path after being compressed.

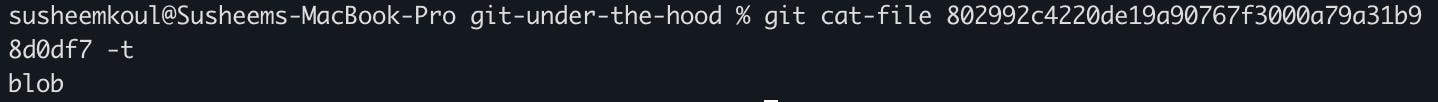

As we will see soon, the directories are also given the same treatment, i.e., they are hashed and the stored in the objects folder. In essence, this objects folder is a key:value store where the key is the hash generated from the stored object and the value is the object like file/directory etc. Git uses several types of objects and we will cover some core ones here. You can use the git cat-file command with the -t flag to check the type of an object. Let’s run it on the file we created just now

You can see that the type is blob.

Blob represents a file in git’s object store. This can be a normal text file, an executable file etc. The blob file doesn’t contain its name. It just contains its contents and other basic information like access control flags etc.

So, getting back to what happened when we ran git add, we can reason that git would use the git hash-object command on the file to hash it and write the results to the objects folder. It would also add the file to the staging area. There is a command git update-index which can actually do the addition to object store as well as updating the index area in one go. The syntax is “git update-index <--add|--remove|--replace> <filename>”. You can use it to add / update the file from working directory to the index as well as hash it and add it to the objects folder.

What happens to the .git folder when you run git commit

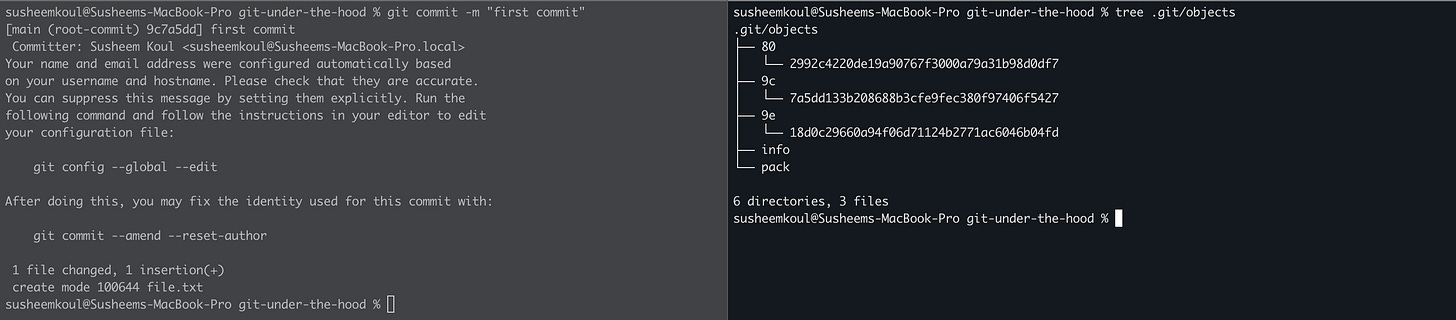

Let’s switch gears to the commit process now. We already have our file in the index. Let’s commit and see what happens to the .git/objects folder.

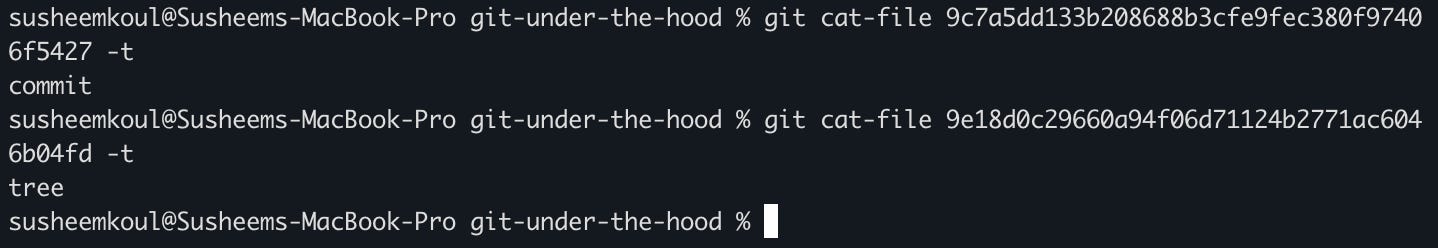

There are 2 new objects created now. The 9c7a5dd133b208688b3cfe9fec380f97406f5427 and the 9e18d0c29660a94f06d71124b2771ac6046b04fd. Let’s analyse what they are by using the git cat-file command with the -t flag that tells us the type of the file.

So we now have 2 new types of objects in front of us. Let’s explain them

The tree object

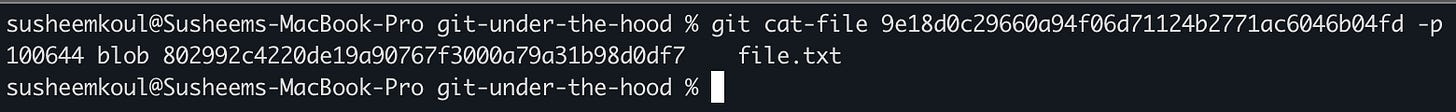

A tree in git represents a directory structure. Tree objects internally contain a list of directory entries which are all pointers to other blob or tree objects. This pointer is nothing but the hash of the blob or the tree that is referenced. Along with the pointer, the directory entries also contain the name of the file/folder represented by the blob/tree. Finally, there is some meta information like the type of the object etc. Let’s see this all by running git cat-file on the tree object

Since tree object contains other trees, it provides support of nesting and thus allows you to have a proper directory tree for your project.

Every resource in your project folder eventually resolves to a tree or a blob object in git.

The commit object

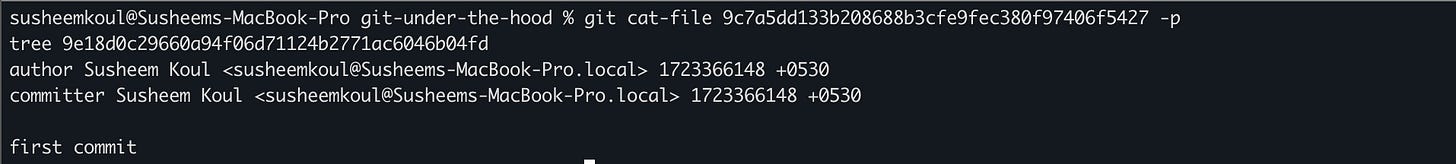

Let’s have a look at the commit object by git cat-file'ing it.

This seems mostly self-explanatory. The commit object contains

author / committer of the change (this can be different under some circumstances, read up online if interested)

a reference to a tree object which forms the root of the project directory tree

the commit message

<optional> pointer to parent commit

So, all-in-all, a commit essentially points to a tree object and the tree object points to further blob and other trees to construct the full project folder structure. When you push another commit, the new commit will also have a pointer to the previous commit so that you can form a history of commits and see how the project has evolved over time.

You can also read up on the

git write-tree/git commit-treecommands that work under the hood when you do a commit. In short, the write-tree command will create the tree object from all the files in the staging area and store it in the object store. The files in the staging area might be in nested folders so the command will create those nested trees too. The commit-tree command will create the commit object and point it to the given tree and optionally a parent commit.

What will happen if i change my file contents?

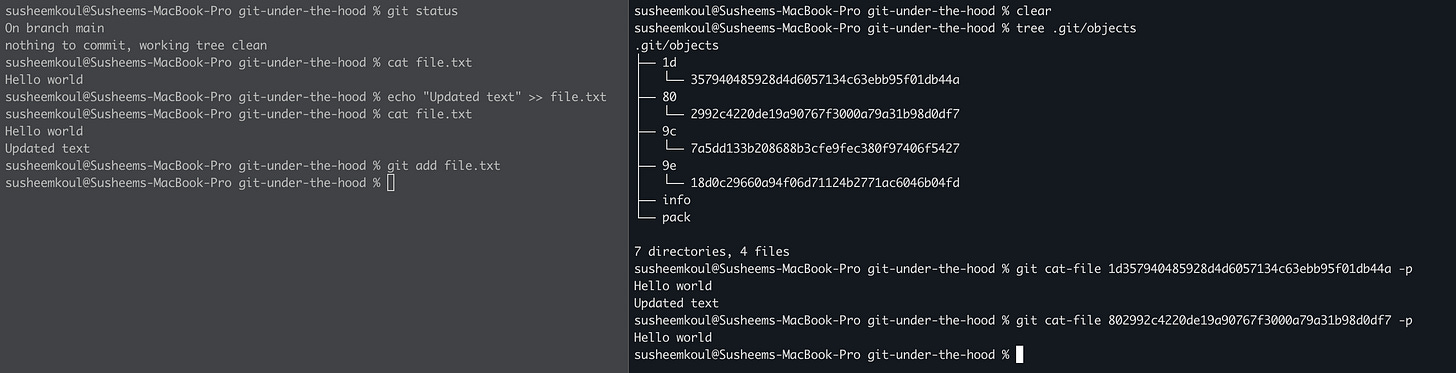

Well you’d expect git to somehow store the old and the new variation of the file right? In the SVN Data Model article, we saw that SVN stores the reverse diff from the latest state of the file to the previous state and creates the previous state by applying the diff as a patch. Git doesn’t store diffs. It stores each file as its object blob object in the object store. Let’s give it a try

We’ve appended some new text to our committed file (remember the original file was represented by the blob : 802992c4220de19a90767f3000a79a31b98d0df7). Now when we do git add file.txt, under the hood, git hashes our files contents and gets a new hash value : 1d357940485928d4d6057134c63ebb95f01db44a. A new file is stored in the objects directory inside .git with the updated contents but you can see the old file and its hash are still there.

Because git stores entire objects and not diffs, checking out an older commit is relatively faster as we don’t have to “construct” the older variations of the files by applying diffs. But this does lead to increased storage consumption. Git gets around this as well by conditionally storing diffs if it makes sense. Read up on pack-files if you are interested or wait for the next article ;)

TLDR

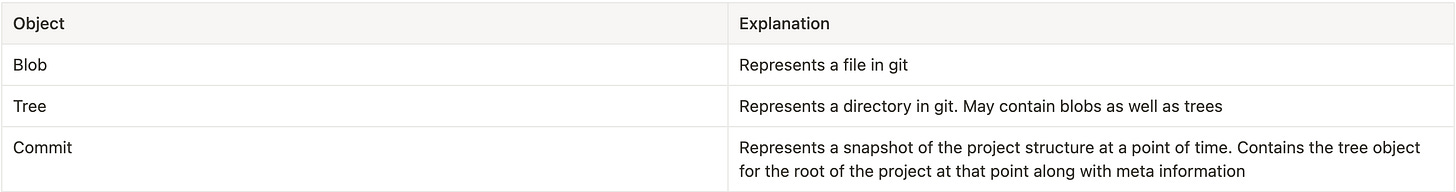

We saw multiple git objects and commands in the preceding sections. Let’s summarise them

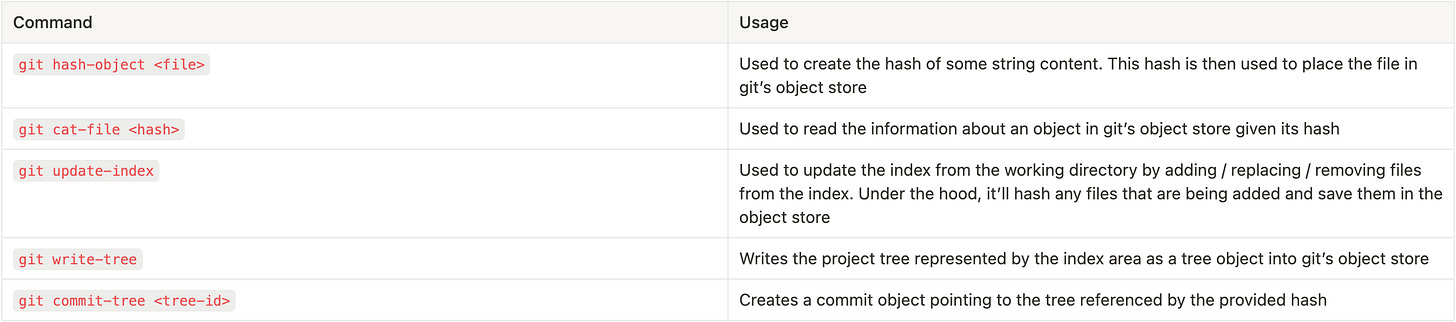

Let’s summarise the low level commands too

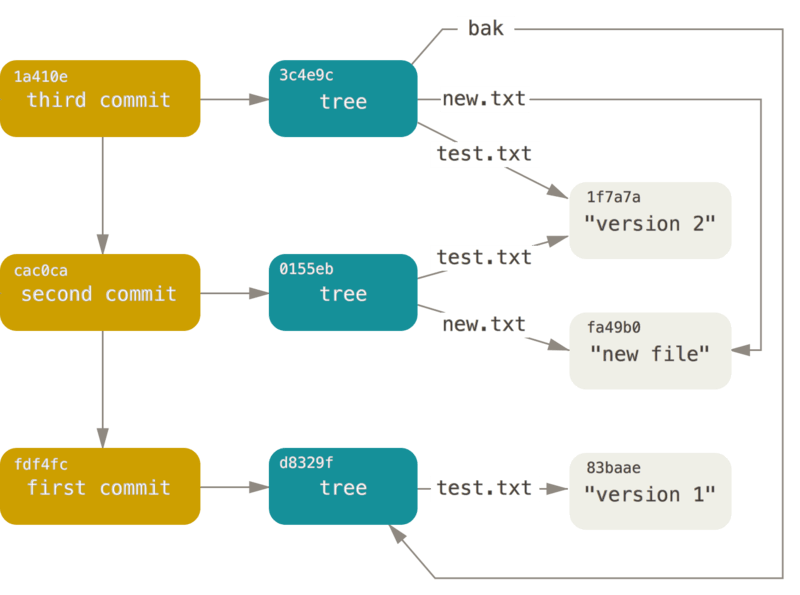

Infographic (credit to https://git-scm.com/)

Each commit points to a tree object and conditionally a previous commit

Each tree points to blobs or other trees and acts as a folder

Each blob represents a file and contains the actual file contents

Old Blobs / Trees aren’t deleted when file / folder contents change. Git simply creates new versions of blobs and trees and the newer commits use these objects instead of the older ones.